Biography

Biography of Jacques Cloarec

March 1995

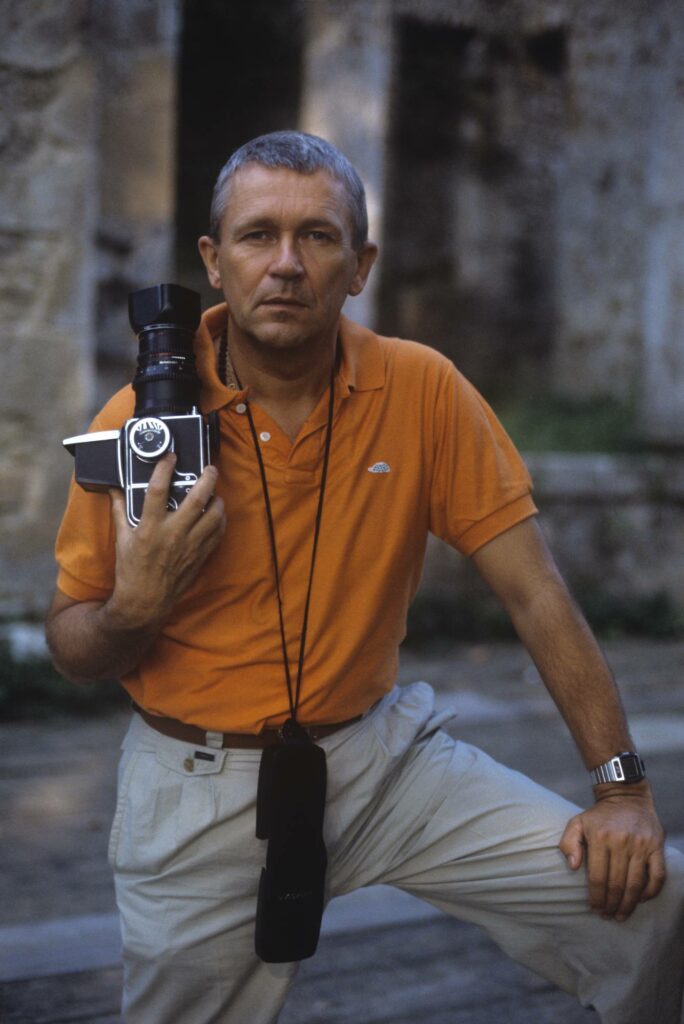

Jacques Cloarec @Angelo Frontoni

Jacques Cloarec – a Breton as his family name suggests – was born in Brest in 1938 under the sign of Pisces. He began his professional life as a schoolteacher in Brittany, where he took a keen interest in Celtic folklore and created and directed several groups of dancers and musicians. In 1960, he left to teach in Paris, and later took part, unenthusiastically, in the Algerian war. In 1962, he met Alain Daniélou, who had founded the Institut international d’études musicales comparées in Berlin.

He lived in West Berlin for fifteen years, then five years in Venice, where Alain Daniélou opened a branch of his Institute. His first job was to classify and record an important collection of photographs that Alain Daniélou and Raymond Burnier – the friend with whom he lived for over fifteen years in a mansion on the banks of the Ganges at Benares, a Swiss photographer and member of the Indian archaeological service – had gathered during their time in India. Never having visited India himself, Jacques Cloarec became familiar with the architecture of most of the great medieval temples, notably those of Khajuraho, Bhuvaneshwar and Konarak, as well as a dozen lesser-known temples such as Aihole, Ossian, Sirpur, Deogarh, Chandpur, Amarkantak, Parasnath and Abu, Sarnath and Sanchi, and so on. Thanks to this photo collection, he viewed the whole of India in spirit, since Burnier and Daniélou had brought back documents from Kulu, Malabar, Almora, Nagaland and Tamil Nadu. He also accompanied groups of classical musicians invited by Alain Daniélou to tour Europe, including the Dagar brothers, Sharan Rani, Pattadmal, Lakshmi Shankar, as well as groups of dancers, the Kathakhali troupe from Kerala Kalamandalam, Yamini Krishnamurti and others. He helped organize Indian music and dance festivals in various European cities, and became secretary of an association of directors of the most important European festivals, aimed at giving concrete expression to Alain Daniélou’s desire to invite Indian classical musicians and dancers to the same major events as Western musicians and dancers.

From 1965 to 1980, he was technical director (with Alain Daniélou as artistic director) of the prestigious UNESCO collection of traditional music records, reissued by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, with recordings by him of a large number of musicians. From his travels, he built up an extensive collection of photographs of landscapes, architecture and, above all, of dancers and musicians from the East in general and India in particular, which have been reproduced in numerous encyclopedias and music magazines, as well as on the cover of many traditional music records.

In 1980, Alain Daniélou decided to retire to a place near Rome. Jacques Cloarec gave up his post as Secretary General of the Berlin and Venice Institutes to become Alain Daniélou’s collaborator in his work as a writer. It was during this period that Alain Daniélou wrote many of the works for which he is famous. Throughout this period, Jacques Cloarec acted as Alain Daniélou’s literary agent, publishing his works. When illness overtook Alain Daniélou, Jacques Cloarec remained at his side until his death in January 1994.

During his long stay in Italy, Jacques Cloarec also became interested in the musical aspects of Italian theater. In particular, he photographed the performances of composer Sylvano Bussotti², in Palermo, Florence, Verona, Rome and elsewhere.

Since 1985, the great choreographer Maurice Béjart¹ repeatedly allowed him to follow his productions, including Le Martyre de Saint Sébastien and Kabuki at La Scala in Milan, both dominated by Eric Vu An, La Métamorphose des Dieux in Brussels, dedicated to Malraux, and also 1789 et Nous, a Béjart¹ Ballet Lausanne production at the Grand Palais in Paris.

A member of the Salon d’Automne de Paris, Jacques Cloarec has exhibited his photographic work there every year since 1982. In 1984, at the Genazzano Festival near Rome, he exhibited his tribute to Sylvano Bussotti², an exhibition that was completed and repeated in L’Aquila (Italy) in August 1987, and at the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi in Florence in May 1988 for the Maggio Fiorentino. His first major retrospective exhibition took place at the Galerie Régine Lussan in Paris in November 1986, as part of the prestigious “Mois de la photo”, under the title L’Opéra à Nu, Entre Corps et Décors. The Salon d’Automne in Paris paid tribute to him in November 1988, with Images-Grimages, Les maquillages de théatre.

As Alain Daniélou’s executor, Jacques Cloarec has endeavored to keep Daniélou’s work available to those seeking a fuller understanding of orthodox Hinduism and its extreme tolerance and, in particular, certain forms of Shaivism, as well as those seeking to understand the world around us.

Jacques Cloarec has supervised the classification and recording of the extensive documentation left by Alain Daniélou, collaborating with the Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne for the photographic material (over 8,000 negatives) and, for the texts, with the Cini Foundation in Venice, to which Alain Daniélou bequeathed his extensive library containing a number of unpublished manuscripts on Indian music. He has also collaborated with UNESCO and the International Music Council on the reissue of record collections; he has coordinated the work of three French specialists, Michel Geiss, Christian Braut and Jacques Dudon, on the design of a new musical instrument based on Alain Daniélou’s theories, and he has spurred the republication and translation of Alain Daniélou’s works, the latest of which – and not the least strange – being the musical scores Daniélou composed for the dances he performed in the ’thirties.

Alain Daniélou’s many commemorations include two exhibitions in Venice in March 1995 (Living in India, an exhibition of photographs by Alain Daniélou taken in the 1940s, and an exhibition of memorabilia, including letters from Tagore, Indira Gandhi, etc.), an exhibition of drawings illustrating his world tour in 1936, and an exhibition of watercolours at a gallery in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Paris.

Collaborator and pupil of Alain Daniélou for over thirty years, steeped in Hindu philosophy, culture and religion, Jacques Cloarec now devotes his time to conveying the concepts his master instilled in him.

1. List of Maurice Béjart ballets photographed by Jacques Cloarec.

Chaka (January 1989, Grand Palais, Paris), Oiseau de feu (March 1989, La Fenice, Venice), Sept danses grecques (May 1989, Paris), Kabuki (September 1986, La Scala, Milan), Kabuki (October 1987, Chatelet, Paris), Métamorphose des dieux (23 October 1986, Brussels), Piaf (June 1989, Paris), Chant du compagnon errant (April 1987, Paris), Trois pièces pour Alexandre (April 1987, Paris), Feminin masculin (April 1987, Paris), Mephisto Walzer Les Chaises (April 1987, Théâtre musical du Châtelet, Paris), Martyre de saint Sébastien (June 1986, La Scala, Milan), 1789 et Nous (May 1989, Grand Palais, Paris), Arepo (Spoleto), Bolero de Ravel (September 1986, Crema), Mishima (1989), Baisée de la fée (July 1988, Rome), Sacre du printemps (July 1988, Rome), Bhakti 1 and 3 (July 1988, Rome).

2. List of Sylvano Bussotti’s productions (as composer, set designer, costume designer and/or director), photographed by Jacques Cloarec.

Le racine (Milan, Piccola Scala, 1980), Fedra (Rome, Teatro dell’Opera, 1988), L’ispirazione (Florence, 51st Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, 1988), L’incoronazione di poppea by C. Monteverdi (Trevisto, Teatro Comunale, 1975), Simon Boccanegra by G. Verdi (Turin, Teatro Regio, 1979), Otello by G. Rossini (Palermo, Teatro Massimo, 1980), Carmen by G. Bizet (Susa, Teatro Civico, 1980), Rappresentazione di anima e corpo by E. de’ Cavalieri (Siena, Teatro dei Rinnovati, 1980) Turandot by G. Puccini (Torre del Lago, Puccini Festival, 1982) Tosca by G. Puccini (Verona, Arena di Verona, 1984), Ulisse by L. Dallapiccola (Turin, Teatro Regio, 1985), Turandot by G. Puccini (Rome, Teatro delle Terme di Caracalla, 1985), La Gioconda by A. Ponchielli (Florence, Teatro Comunale, 1986)

Aida by G. Verdi (Rome, Teatro delle Terme di Caracalla, 1987).

Interview with Jacques Cloarec about the profession of photographer — France Inter (November 11, 1986)

Gentlemen, I’d like to give you another example of this Month of Photography, and that’s the exhibition starting tomorrow at the Régine Lussan gallery of works by Jacques Cloarec devoted exclusively to the Opera, both on stage and backstage. Sophie Dumoulin asked Jacques Cloarec to talk to us about his exhibition, his choice of models and his approach to photography.

Jacques CLOAREC: For the last ten years or so, I’ve been photographing all the shows by a single director, the Italian avant-garde composer Sylvano Bussotti, who does a huge amount of directing in Italy but is little known in France. And I thought that French audiences would be interested to know about his work.

He is very baroque in his designs and has performed on Italy’s main stages. So I followed him to the Verona Arena, where he opened last year’s season with Toska. I followed him to Palermo for Rossini’s Otello, to Rome for Simon Boccanegra, and to his own works too, since he himself has written several operas.

I don’t think of this work as a photographer who arrives on the day of the dress rehearsal to photograph the show and then moves on to the next one; I always try to live the show for about a week. In other words, I live with the company, I attend all the rehearsals without costume, in costume. I go and see the tailors who make the costumes, I take the photos at that time, I see the director in what he is trying to do and I photograph certain parts of the shows that particularly interest me.

Sophie DUMOULIN: So, do you sit in the auditorium or in the bullring?

Jacques CLOAREC: Yes, the main thing is not to be seen because the state of tension that exists on a stage when an opera is being staged is something that absolutely fascinates me because when there are 3 to 400 people to bring together, everyone is in a state of agitation and you have to manage to coordinate everything. If, on top of that, there’s a photographer in your way who’s there every minute, he’s very, very unpopular. So you have to make yourself very small, very small, dress in very dark colours to make yourself seen as little as possible, and then go in very slowly, using very quiet cameras. I use a Leica to make myself as inconspicuous as possible and that’s it.